As Richard Rumelt describes in Good Strategy, Bad Strategy, many organizations have a strategic planning process that gathers all the biggest activities seen by different parts of the organization as urgent or important and brings them together as a list of “strategic priorities.” It is a bottoms-up exercise of what people hope will happen, usually followed by an effort to apply some type of prioritization to all those activities.

Too often, these efforts miss the critical, intellectual bridge that helps leaders make the best inclusionary and exclusionary decisions about where to focus the company’s resources. This missing gap stems from the following:

- No Diagnoses: A lack of analysis to articulate the true, underlying problems or obstacles to overcome, resulting in a focus on symptoms versus root causes

- No Guiding Policy: Resulting in a laundry list of things to work on, but unclear (or assumed) reasoning why or why not

Without upfront analysis to drive alignment around a core set of principles for decision-making, organizations may struggle to define coherent plans, as they lack the tools and discipline to make hard choices, particularly about what not to pursue. This lack of clarity is particularly crippling for technology organizations since strategic technology decisions often involve investments that are large and hard to reverse.

Why decision principles are key to good strategy

A technology organization and its technology strategy need to be inextricably intertwined with the overall business strategy, and clarity for the strategic decisions of a technology organization needs to be well-defined, well-reasoned, and well-aligned from the outset.

Decision principles are guardrails that help leaders evaluate whether policies and actions under consideration move the organization closer or further from its ultimate goal. They provide instructions – a direction to move towards – and, by extension – a direction to avoid or move away from.

Well-stated principles incorporate an understanding of the key challenges hindering the organization from reaching goals and the opportunities to exploit. They provide but simplify the resulting decision-making implications to something easily understood and applied during strategic planning. Being relatively simple and straightforward, they help leaders coordinate across departments (and functions!) so that actions are cohesive and don’t undermine each other.

Typical decision principles for technology strategy

In our experience, there are some fundamental questions that organizations tend to wrestle with that end up being the center of our Technology Strategy efforts. If they are not already resolved, these are hard questions that must be aligned on with stakeholders across the business. Here are some of the most common initial questions whose answers can turn into decision principles.

- What’s our primary focus as a technology organization? Of course, every company wants its technology organization to be low-cost, responsive, and innovative, but it is impossible to be great at all three, so priorities need to be set.

- Are we a software development shop or a services organization? Or…when do we buy versus build core systems? Companies need to decide whether they need to build software products to differentiate in the market, or whether they just need to integrate packages well.

- As an enterprise, do we modify systems to processes or modify processes to systems? In an ideal world, this decision principle is closely related to a buy versus build conversation because it rarely makes sense to significantly modify systems to unique processes when you are paying for the value of industry standards.

- Do we push the organization to enterprise standards or allow business units to have unique technology stacks? Related, are our technology resources centralized, decentralized, or federated? Companies must be clear about what systems, processes, and resources are standard and what can vary by divisional needs.

- Are we following a product development or project planning philosophy for investment and execution? The shift from project to product continues, but many organizations are only halfway committed. A product mindset must be aligned from technology investment all the way through how the organization operates.

Identifying your decision principles

The work to find the root questions and evaluate alignment on decision principles begins at the outset of starting a strategic planning project or engaging in a strategic planning conversation. While building kickoff presentations, reviewing past artifacts, and conducting initial conversations, we are probing to uncover those questions and evaluate organizational alignment on the answers.

Some teams are tempted to wait until a full current-state assessment is complete, and others are tempted to push to recommendations before the thinking has been pushed far enough. The magic happens when you keep pushing to questions that are really at the heart of the challenge and reach alignment in time to incorporate the principles into the final assessment and subsequent future-state discussions.

You will be on track to identifying key decision principles when it feels like choosing a path in one would significantly impact the organization’s overall direction. Often, there are differences of opinion on how to move forward; often, there are signs of split priorities through current work and plans.

It may seem obvious at first how to establish these principles – just choose an answer and declare that direction as the principle to move forward. However, there is a complication that these principles are broad-reaching, and they are choices – choices that involve saying ‘no’ to some things.

Typically, the organization is pulling in different directions because conflicting answers seem right under different situations or at different moments in time. The challenge, then, is not only deciding on the principle to establish (i.e., answering the question) but deciding in a way that gains alignment with all those who must be on board and then communicating with all those who need to know.

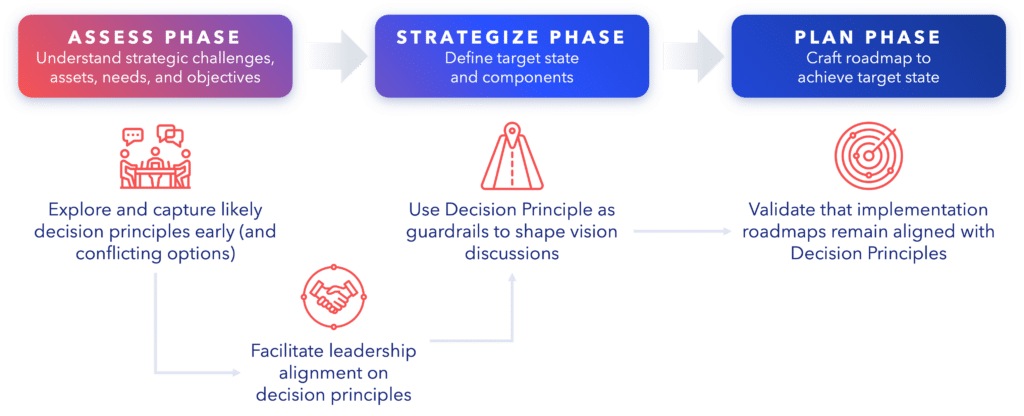

While every technology strategy project we take on is unique, we often find that in the middle of it, often late during the “Assess” phase or early in the “Strategize” phase, we are working on deciding and aligning on the decision principles. Sometimes, we know the core questions to answer coming into the project, and sometimes, the core question(s) are discovered as we dig into our assessment.

However, once they are identified, we tackle the open questions with an intentional process. We lay out assumptions, design alternative options, and then evaluate each option’s pros, cons, costs, risks, and success factors. Through this process, we gain input from other stakeholders so that they understand the tradeoffs and can support the decision moving forward. Then, we lead the group through making a final decision.

Often, there are multiple viable paths, and we, as consultants, help analyze but do not make the decision. Depending on the type of decision, this analysis could be a slide or two in a presentation or a complex business case. In most cases, though, it is the facilitated leadership discussion that is crucial—that is often the pivotal moment where the executive team finally aligns on how to move forward.

Finally, once the decision principles are decided, they must be communicated. Having everyone in the organization understand not only what they will be doing but also why their leaders are taking that path will reduce friction and help build support for the strategic direction. The communication typically starts as part of the strategic plan readout but needs to continue to be emphasized over time to be integrated fully.

Conclusion

Through our years doing technology strategy, we have stepped into organizations experiencing all kinds of challenges—from surface challenges like demand management and productivity to undercurrent challenges like lack of trust and unclear accountability.

Much of the frustration stems from the technology organization being pulled in too many different directions. Clarifying the root questions and then pushing towards alignment on strategic decision principles can improve the flow and support around ongoing decision-making and help ensure that planned work will bring the most organizational value possible. We hope this kind of thinking is helpful for you in your efforts, and we welcome the opportunity to be a thought partner with you anytime.